%20(4).png)

%20(4).png)

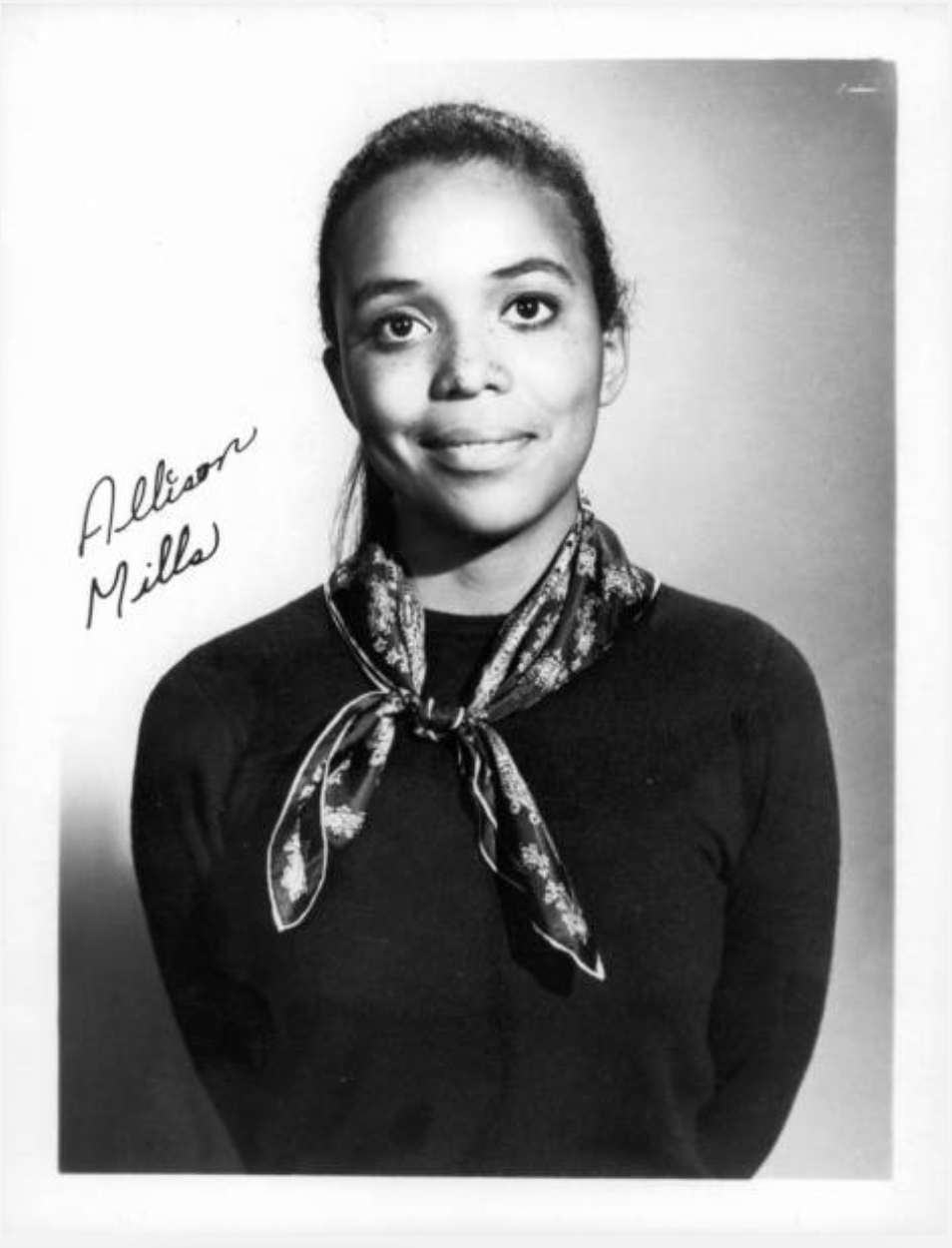

Last season, TBR commissioned the journalist and essayist Lynell George to write about Francisco, Alison Mills Newman’s 1974 autofiction gem that was recently reissued by New Directions. Mills Newman was so delighted with George’s essay that she reached out to ask if the two might be in conversation. We were also delighted; it seemed only fitting that TBR host these two writers we admire so much.

What follows is the first significant interview to trace the early years of Mills Newman’s astonishing career, from helping to break the color barrier as a childhood television star in Los Angeles to opening for Ornette Coleman in New York to being discovered as a writer by Ishmael Reed in San Francisco. Along the way she crossed paths and collaborated with a who’s who of Black luminaries: Frank Silvera, Nichelle Nichols, Beah Richardson, Don Cherry, and David Henderson, to name just a few. And of course the filmmaker Francisco Newman, her novel’s eponymous protagonist and eventually her husband.

Their conversation is also about the artist’s voice: finding, following, and sustaining it through life’s twists and turns. “Do you see how I answered the call?” Mills Newman asks. “I was writing even though I didn’t know it was a book, I was still writing. I stuck to it with all the shenanigans and ups and down, and going here and there, I stuck to it.” -clr

Alison Mills Newman: Well, good morning to you. I’m just overwhelmed with joy and thankfulness for this opportunity to be able to share the story of Francisco.

Lynell George: Thank you for being such a keen observer and interpreter. I just am grateful that that book exists. I want to talk to you a little bit about your life as a reader and writer: What sort of reader were you growing up?

AMN: Oh, I read E. E. Cummings, Emily Dickinson, Edna St. Vincent Millay. I was exposed to Sonia Sanchez and Nikki Giovanni later on in my twenties. My mother introduced me to Langston Hughes and Phillis Wheatley. As a child somehow I read Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights. I remember reading Native Son, when I started acting in the workshop with American Theatre of Being.

LG: That was in New York?

AMN: No, that was in Los Angeles, on Robertson Boulevard; when I was twelve I decided I wanted to become an actress, and my mother found this place for me. It was directed and guided by the great Frank Silvera. He was African American but he had a chameleon physicality — he had many opportunities to work because he could be other nationalities and races. He co-starred in a lot of movies, like Viva Zapata!, Up Tight, Guns of the Magnificent Seven, worked with Paul Newman and all the stars of that day, so he was able to rent this theater. Everyone was there, struggling actors before their big breaks: Maya Angelou, Nichelle Nichols, Max Julien, everybody. An incubator of talent. They were all beautiful, important, geniuses. My mother would have them over for dinner. When I look back, I’m in awe of the people that I was exposed to — and even though they were much older than I was, they never condescended to me. They talked to me like I was an adult, they considered us all gifted, all in this garden together.

LG: How wonderful.

AMN: We did a play called For My People which consisted of diverse Black poetry. Maya had a poem, I had a poem, Beah Richards, Dick Anthony Williams, Max Julien; we traveled to different colleges fifty, sixty years ago, performing this poetry. So, I was exposed to Black poetry and I was exposed to James Baldwin very early. I understudied in The Amen Corner [by Baldwin] when I was sixteen years old. There’s a role for a little prostitute who walks in with a one-liner. I was given that role one night because the actress who was supposed to do it didn’t show up. I was often sitting in the theater and just listening to the dialogue, learning from the actors, taking note of timing, rhythm. I grew up studying and performing Romeo and Juliet.

LG: This was the early seventies?

AMN: Yeah. I had the lead role in Our Town, produced by C. Bernard Jackson’s Inner City Repertory Company in 1968. So, I would say being into poetry in my home life, but also through my acting, brought me into the world of literature. I met writers and musicians in this milieu of actors, the greatest of them at that time.

%20(4).png)

LG: When did you know that you were a writer and how did your writing begin to express itself?

AMN: Oh my, yes, yes yes. I was an introverted child even though I was extraverted onstage. I was a very private little girl. When I was around sixteen, in 1967 or so, my parents moved from 28th Street to this two-story house in Los Angeles on Westchester Place off Olympic and Wilshire, and there was a maid’s room. Well, we didn’t have a maid. I shared a bedroom with my sister but eventually I convinced my parents to allow me to move into the maid’s room. Down there in my solitude, by the washing machine I just began to think about things and I would write about what I was feeling. But years before that, when my mother started teaching me piano lessons — I found myself creating my own melodies.

LG: How old were you again?

AMN: At the start of it all, I think around ten, and after awhile words started coming to me to compliment the melodies. I came to understand those were lyrics, so I started putting poetry to music. I was just singing my little melodies and my wonderful mother didn’t disdain that. She did want me to practice but she didn’t discourage that. So, I was first a poet and that turned to lyricism and then I began to write short stories.

LG: When you were writing the poetry, were you looking internally, or were you looking externally?

AMN: I think it was a little bit of both. I always remember looking deeply into people. Their eyes, their hair, and their ears, their size. Sometimes in my writing I would compare one of my aunts, or uncles, the way they walked, to a turtle, or to a swan. There were similes that I didn’t know were similes: my aunt is like a swan, or my uncle has a big nose like a whale, or an elephant. That would be more outward. Then inward: I was not in love as a child, but I always wanted to be in love, and I always loved love. One of the first poems I wrote once I got into the workshop with Frank Silvera and I was a little older was about a secret crush I had on this older man Don Mitchell who later became the co-star of Ironside. We would do scenes together and he’d say, “I’m going to marry you when you grow up.” And I believed him!

LG: Aw.

AMN: Silly child that I was! I think I wrote a poem that turned into a song, about being in love with him, at least I thought I was in love with him.

LG: Do you think the being in love with love came from reading poetry, or movies, or just this innate thing inside of you?

AMN: I think I was born with it. I didn’t know what love was, but I believed in it… yeah, but surely digesting poems about love touched me. I was in love with the idea of it. Loving creation, loving the wind, loving fall, loving movement — so much of my soul loved creativity, loved people and the way they looked, their eyes, their nose, loved their skinny legs, or their big legs. It was never with judgment or negativity: my vision, my heart through my eyes, was always acceptance, that I appreciated the differences. But I will say I was heartbroken when one of my fellow actresses, a Black lady, she wanted to be a star and so forth — we were rehearsing a skit together at the workshop and she showed up one day Lynell and she had her nose operated on.

LG: Ah. And for someone like you who studied these things and saw them as part of her, that had to be shocking.

AMN: It was so shocking. I didn’t say anything to her. I’m sure I said something with my face, and my eyes, I was just so dumbfounded. Why would she change her beautiful big nose? And the nose that she got didn’t fit her eyes to me, it didn’t fit her mouth — it didn’t fit her! She was so beautiful the way God made her.

LG: Right. There is that wonderful part of Francisco where the narrator delves into the frustrations of wanting to be able to hold on to her essence, to herself and looking at how women had to alter themselves in order to work. To live.

AMN: Heartbreaking. Changing who you are just to fit in to a society that rejects your beauty is not something that my parents taught me. The pressure of it all, don’t believe the lie. My mother was a darker skinned beautiful Black woman, my father was of lighter complexion, and my sister and brother were of a darker complexion. I took more after my father. My parents always told us that all our colors were beautiful, even before “Black is beautiful!” That all people are beautiful. They were emphatic to teach us that we were all created by the same God, even if some people may not know it. You are a child of God. Period. My mother was an activist. Marched with Martin Luther King.

LG: So, they instilled self-worth very early on and you watched by their participation.

I want to swing back to what you were talking about with artistic forms. You were writing poetry and you started writing short stories, you said. Were you a big journaler as well? Did you keep a diary?

AMN: I think if I was a journaler it was a fusion, hidden in a poem or a short story. I didn’t do what I did in Francisco where I just outright, boldly was writing my everyday encounters.

LG: You were also a musician, and a singer; it sounds like everything was informing everything else.

I feel the music and musicianship in your writing in terms of rhythm and pace and the way my ear listens for it — I anticipate as you would in music because already, you’re floating in this meter, in this rhythm. It’s so intoxicatingly beautiful. You really do weave a spell in your writing.

AMN: Thank you so kindly. That brings tears to my eyes. I thank God for the foundation my mother gave me, learning how to read music, and the foundation of prior writers that I was exposed to. I practiced their style of writing. But early on, I was hearing a different music. I was hearing a different sound… my inner rhythm and beat.

LG: What were you hearing? Can you even describe it?

AMN: It’s a dissonance, off-key, vibrations, movement, like it must explode… a feeling that is not restricted by what is established or known to be right. I know the established way, I’m not ignorant of it and it too is beautiful, but that’s not what I often hear. I hear sometimes words flowing calmly but then breaks/cuts/silences/mountains beside gentle rivers, suddenness… what appears to be disorder is sometimes order to me… sentences without punctuation because percussion is the punctuation. When I was writing Francisco, rhythm/syncopation was the punctuation sometimes. Maybe it’s the African blood in me, inner drums, but also an inner classical cello.

Less is sometimes more revealing. I am always hoping to serve the reader with being there, seeing it as cinema. I seem to be always in the hybrid lane, poetry and prose fusing together. When I went to New York, when I was nineteen, I had a bond with Ornette Coleman; he told me how his music was totally rejected by his mother, church, the music world of his beginnings. But he pressed on... we could talk about everything for hours. Time passed like minutes because of the initial connection of dissonant melody/chords that we identified in each other’s music. You have to hear it and trust it. It’s like thunder, like the sun, like the rain. It’s like elephant feet.

LG: I love this! Elephant feet. It’s true.

AMN: The writing in Francisco, oh my goodness… that time, that moment, it was magical. It was embedded in this gift of creative relationships and I think the excitement for me being free of the confusing sexual exploitation and celebrity exaltation I experienced in Hollywood. The adjustment the narrator makes in terms of supporting Francisco in the making of his film is a position the narrator understands explicitly as an artist. For instance, when I was preparing for my role in Our Town I wouldn’t have dreamed of having another human being in my life that I had to pay any attention to; even if I was married, my husband wouldn’t see me for a month or two because of the consecration and focus I demand of myself in the process of becoming the character, learning the lines, etc. I often need to create in secret. For Francisco, in that season of his life, to include me was an inclusion that I understood as an artist. Here was this beautiful soul working on his film, fighting for it — and I understood his fight, and how to be in his life and how to not be in competition with him, nor did I want to be in competition. I understood the beauty of support because in my life as an artist, I was supported by my family and my fellow actors… and I just understood the struggle for the artistic dream and how hard it can be.

When I opened up in Our Town for instance, everybody was there in the audience, and the first TV show that I guest-starred in, Mr. Novak, Maya Angelou, Nichelle Nichols, Kyle Johnson who starred in The Learning Tree — everybody was there at my parents’ house to watch it together. That’s all we did was support and believe in each other because it was huge to be on TV. Nobody Black was on TV hardly, it was deemed impossible. So when Nichelle got Star Trek and Don Mitchell got Ironside and Beah Richards co-starred in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, it was nothing but love — and that is love, to support someone in their dream. I didn’t experience any jealousy. I was a child, so I was supported by my parents, but mostly everybody else was a starving, striving artist and everyone helped each other.

And having escaped Hollywood when I met Francisco, I had had enough attention. People don’t understand that. I was sick of attention. I sought very much to just “be.” Fifty years ago to be who I was [the first Black teenage actress on a television series, Julia] — I remember I was in a store once with my mother and people started crying, started lining up for autographs.

LG: Oh my goodness!

It sounded like, from the book, you were filling your well. It put you in these other kinds of worlds and that way you observe people — you went deep and learned things from the adjacency to Francisco and his circle, and your circles intersecting.

AMN: Yes. So many people I learned from, so many I can’t even really remember… so much newness came to me from all the brilliant, good souls and I was enraptured and teachable. In Francisco’s directing/painting/artist world there was Ishmael Reed, Joe Overstreet, D Stevens, St. Clair Bourne, and all the people I met through Ishmael… like Toni Morrison, James Baldwin, William Demby, Steve Cannon. In my circle lovely Joy Bang and generous Ed Pressman — he was a major film producer — befriended Francisco. That was his Malibu home that we lived in. I was a by-default co-producer: we were guerilla warfare/making a film independently where everybody does everything. The producer cooks. Nobody is the star. Everybody’s in the trenches. Everybody is in the same place for the love of it. Acting for me was always for the love of it. God granted me success, He granted me a portion of stardom, but I don’t think I really understood as a kid that that was part of it. It was just something that I loved.

AMN: That love protected me from selling my soul to the devil. That was a major crossroads, virtue versus cheapening the gift that God gave me and the vision that I had. There was much about virtue I was incognizant of for sure but some I was aware of and I was in search of more. I wanted to do good with my art, and so did Francisco, and that was our bond. It was a loving, intellectual, artistic connection. We weren’t even noticing what we were doing, we were just doing it.

LG: We don’t realize as we’re going through it, this moment won’t continue forever. It sounds like everybody was so very present, and so all in.

LG: And that love carried you through it, I see that.

AMN: Everyone! These people, Maya Angelou and Max Julien, they wanted to change the world, you know. They wanted to add their beauty to the world. It wasn’t about instant gratification. It wasn’t about your body, your flesh, it was about the spirit. That time, the sixties and the seventies, it was a search — the hippies, and Black Power, and the Black Is Beautiful movement, the music of Joni Mitchell, Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix, Crosby, Stills & Nash, Marvin Gaye; of course James Brown and Martin Luther King and, I don’t care what anybody says, Huey Newton before he was infested, addressing police brutality toward our people — it was beautiful what he was doing. A people have the right to self-defense. And it was necessary, given the way Black people have been treated in this country— now we can prove it with these cellphones that we were being terrorized and being killed. Unfortunately, young gangbangers in the eighties added terror to our community doing drive-by shootings. After Francisco and I were called to ministry we were sent to do missionary work in the inner city.

I remember driving from Nichols Canyon home to my parents house; they lived in this well-off, predominantly white Jewish neighborhood, Westchester Place. I parked my car and two policemen appeared out of nowhere asking me aggressively, “What are you doing in this neighborhood?” One put a cocked gun to my neck.

LG: Alison! To your neck?

AMN: To the back of my neck. I was nineteen years old.

LG: And this was the seventies. See people don’t believe. Oh, Alison.

AMN: They don’t believe! This drama of just walking on the earth.

Very meekly I said, “My parents live in this house.” “Your parents can’t live in this house!” Then the other policemen looked at me, and then he looked again, and he said, “Oh, I’ve seen her on TV. She’s a star.”

LG: So it switched like that?

AMN: I was co-starring on The Leslie Uggams Show. And suddenly I’m a human being. Suddenly I have value because I’m on television. How wicked. If I had just been what I was in their eyes, just a nobody, I might have been dead. I might not even have made it to my mother’s front door.

LG: I was thinking exactly that. If he hadn’t recognized you and if you had said the wrong thing — the fact that they cocked the gun.

AMN: Can you imagine all the Black girls and boys who have been killed and nobody even knows? My brother was a basketball genius — Black people are geniuses — and the basketball coach would tell him to run home for the exercise. One day when he was running home, the police stopped him, Lynell, took him to an alley.

LG: Oh no, no, no, no.

AMN: And beat him bloody for running while Black. My parents were driving all over Los Angeles, calling friends here and there; one of them called my mom and said, “I think I see your son, I think I see Ted in the alley.” That’s how they found my amazing, genius brother. I want the world to know: my brother has gone on to be with the Lord but those experiences, that racism, ruined his life. He was a kid. For years he didn’t know how to manage the pain and fear of it, Lynell. Little Black boys were in alleys being beaten up by police for exercising, for running, for just existing. We had a dream that nobody could see, but we saw it by faith, and we believed. Then the Lord met our dream and America was confronted with the Watts riots and Martin Luther King — and good people speaking up against injustice. That’s the only reason I was on TV, because people threatened to tear America up.

.jpeg)

My mother would not let me forget: “Alison, you are only here because people died for this. Your people died for this, white people died, and marched as well.” She instilled in me that love for my Black people, and to represent Black people in a positive, elegant way. I wish we had more mentors today that would encourage our young artists to instill positive images of Black people, and human beings in general, spreading messages that encourage us to love one another as human family and not hate ourselves or hate one another. So many Black people today are sacrificing their integrity in the hopes that they will get to do what they want to do, but sometimes whenever they get there, their soul is so dead.

LG: That’s right. They sacrifice themselves. Period.

AMN: And they sacrifice what they know is right. I’m so glad at that time in my life, I walked away from Hollywood. I have no regrets. God gave me love that I would never have found there.

LG: He gave you community.

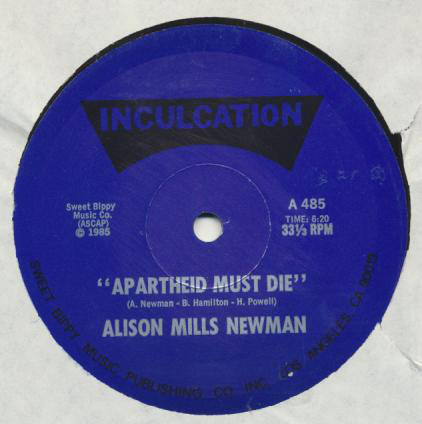

AMN: Yes, He gave me community! You know, this is the thing about Ishmael Reed and James Baldwin. Steve Cannon. Ornette Coleman and Taj Mahal, Wayne Shorter and Joe Zawinul from the band Weather Report, Jaco Pastorius, and so many more. These men of that generation, back in the sixties and the seventies, not that they were perfect, but I hope that anybody reading would understand that they respected me as a human/artist. I really want to honor them. When I went to New York I did a play at Amiri Baraka’s Spirit House with Dick Anthony Williams, a flurry of poetry readings in Harlem accompanied with African drums/musicians, and Greenwich Village at St. Marks Theatre with my dear friend Anne Waldman, and with David Henderson. I opened up for Ornette, Don Cherry, and performed with my own band where saxophonist David Murray sat in a couple of performances. There was a play written just for me that I did off-Broadway, called The Party at Annie Mae’s House, Dick Anthony Williams joined me in that play. None of them ever said, “Well, I want you to sleep with me for this gig.” They respected me. Some of these young artists today, the way they talk about women in their music, I would ask them to think again.

LG: How did you meet Ishmael?

AMN: I met Ishmael because I was living, in sin, with Francisco. Francisco was negotiating with Ishmael to option the rights to his book, Yellow Back Radio Broke Down, so we’d go to Ishmael’s house and his beautiful wife Carla would make us dinner and we’d talk about the movie and Richard Pryor starring in it and blippity blip. All these dreamers dreaming together, just plotting along in a little boat, hoping that it would turn into a big steamer! So that’s how I met Ishmael.

LG: One of the questions I wanted to ask was where you found encouragement. Now, it’s clear, you’ve been weaving this through our whole conversation: these people were mentors, but they also were collaborators.

AMN: They were equals. Art is art. That was the way they looked at it, and boom, that was it. They inspired, encouraged one another.

LG: How did you meet Ornette?

AMN: I met him in New York during my escape. My freedom! My liberation!

LG: That’s a beautiful segment of Francisco too, that vivid, cinematic, section of all these women alison sees in the streets of Manhattan, their faces — like when you were talking earlier about how you looked at an ear, or a nose, or the shape of an eye.

But, Ornette?

AMN: I was living on 77th and Lexington and now, listen to this — my seventies slang came back. I almost said, “Dig this, Lynell.”

LG: Say it! I love it!

AMN: Dig this, Lynell, I’m still relatively well-known but the thing that’s so great about New York is that ain’t nobody nobody in New York, everybody’s somebody. No one is stopping me for autographs or anything like that. Yeah, that was wonderful. One day this Black beautiful woman stops me in the lobby of the apartment building and she says, “I’ve been watching you, and all you do is hang out with white people” — this is true — she said, “When you all get famous, all you do is hang out with white people. That’s fine, but you need to hang out with some Black people for your soul.”

LG: Oh wow.

AMN: I’m nineteen going on twenty. And at that moment my friend I was living with was a Swedish model, on the cover of Vogue, and my whole world was white. I heard the message of this Black lady and I understood. So I said to myself, who do I know in New York that is Black? Dick Anthony Williams and Gloria Edwards were starring in a play on Broadway called Ain't Supposed to Die a Natural Death, written by Melvin Van Peebles, so I found them. And they embraced me. I came to the play where, of course, I met Melvin, but my experience with him I didn’t put into the book.

LG: Oh.

AMN: But Dick and Gloria, I grew up with them at the American Theatre of Being, so they were family — they invited me to stay with them. Nowadays, don’t nobody hardly invite you to dinner after church, much less invite you to come live with them but then people were open and trusting. Through them I met a writer by the name of David Henderson. I played my music for him and he took me on a book tour; very respectfully he said, “I want you to play your music before I read from my books.” And praise God, I did that with David Henderson, a great poet, great writer. Back in those days people just introduced you. It was just living it wasn’t like...

LG: Networking.

AMN: No! God forbid!

LG: I love it.

AMN: Thank you Jesus! I hate networking.

LG: It’s awful. It’s like, no, I was just having a good time, I wasn’t angling.

AMN: Right on, you get it! So, David says, “I want you to meet this friend of mine.” I’d never heard of Ornette Coleman in my life. My parents, they loved amazing Aretha Franklin, Diana Ross — I wasn’t exposed to anything close to jazz if I remember correctly. We were pretty much R&B loving, which was interesting because my melodies were otherworldly. So, David takes me over to Ornette’s loft in Soho, on Prince Street. And I’m just stunned. On all his walls are nothing but African art and African paintings, and this genius man is dressed in silk. His band is rehearsing, Charlie Haden, Ed Blackwell on drums, the great Billy Higgins…playing this beautifully insane music, and I just go wild running through the loft, dancing, belonging. He’s got this gorgeous model girlfriend, a Black African girl, and I’m just running around freely, dancing. They’d been rehearsing for hours. I grew up around discipline, man; discipline is a cousin to true freedom. And when they finish, David introduces me to Ornette and he just looks at me, and he says, “Well, what do you do?” I was running from acting in that moment and I was surrounded by all this amazing music and I just said, “I write songs.” He said, “Oh, well let me hear some of your songs.” So, I’m not planning to do this, I didn’t go to his house with any music on my mind, I was just loving their music and they were loving me loving it. I don’t even know he’s Ornette! Don’t know him from beans. So I’m playing my music on the piano in his loft, and they’re all just, “Ah! That’s so beautiful. That’s so amazing.” So he said, “I want you to open up for me. I’ve got a gig in two weeks.”

LG: That’s incredible.

.jpg)

AMN: I’m just going with the flow... to do it. I’ve been in art all my life, so I’m thinking when I look back at myself, it’s just because that’s all I knew. Music and acting and writing, being on TV, producing, creating, you know. So I just offered what I knew, and the next thing I know I was in his loft, practicing. Living, actually, in his loft, having these amazing esoteric conversations with him and his girlfriend. In the sixties and seventies artists took you under their wing. It wasn’t about sex...I mean, it could turn into that, it could turn into lust or love, specifically in my experience with Francisco. But, what I’m trying to express is that it was a genuine appreciation for the gifts that people had and sharing them with your world. I ended up, a couple of weeks later, opening up for him at the Five Spot. They wrote about me in The Village Voice, there’s a little mention in a review.

LG: Oh my gosh!

AMN: On the night of the performance, I went backstage and there was a guy going around shooting up some of the musicians with heroin, not Ornette. The heroin supplier, or whatever, comes to me and they all say, “No, no, no, no, leave her alone, don’t touch her.” I’d never seen heroin before up close. You know, if people did it in Hollywood, and I’m sure they did, it was a lot more private; and some of them had doctors that shot them up, that’s why a lot of them in California didn’t die. Musicians in New York, God bless them, they were back there getting shot up. But they emphatically protected me… such love. Ornette would tell me warning stories about musicians being on drugs, he knew Billie Holiday, Charlie Parker, and everyone. He did not take any drugs. He was all-natural good.

But, that’s how I met him, I would call it by divine introduction. I needed to expand my territory. That’s what opened me up to Francisco being published, me being redirected, listening to that voice in the older Black woman — because back in the day you walk along the street and if you were famous Black people held you accountable.

LG: They thought of you as one of theirs.

AMN: Yeah, they pull your coattails and straighten you out and tell you how you have to stay in touch. I needed that guidance. You can get caught up and forget who you are and where you come from.

LG: Know thy self. I want to go back to Francisco. How did it begin to take form? It sounds like from the way you work you don’t necessarily sit down with the intention, “I’m going to write a novel.”

AMN: It depends… My art was the art of the relationship, learning and growing in it, embracing people, when I was first with Francisco. The writing came to me like a call. I would feel it… capture these people/moments. I would wake up at two in the morning and this voice is saying, “You’ve got to write it down. Write it down. Write it down!” I would listen, I would see, I would watch. As soon as I got anywhere, like a restaurant, I’d ask for a pen and write on the napkin, on a bag, anything — I don’t know that they had journals then? But I know eventually I bought a pad, paper, kept it organized. That was my discipline then because it was the way I could still be creative and be in this relationship with this beautiful friend of mine and record all of it.

LG: I love this.

AMN: People ask me often how I write and I say, “I just listen.” And I’m a musician, and see, we musicians, we hear. You know? We just hear. It serves me well. It’s about being honest — and not to block myself, to receive. For me it’s also about watching/seeing/painting colors with words.

LG: You know when to pay attention to something as a writer. I so, so, so understand this; the things I’ve done that have mattered the most emerge from inside, exactly this way.

AMN: Write it! When I wrote Maggie 3 my husband and I lived in the country. I was about thirty-five years old and I was still writing with awareness little poems, short stories, and thoughts diligently, some of which Ishmael published in his Yardbird Reader. But one day I was walking along the country road and a voice said to me, “Write a book.” So in that particular case, yes, the goal was to write a book. I didn’t have anything that I felt moved to write about. But I heard a voice. We had a typewriter back then on an old wooden table and I just sat at the typewriter. It began to flow. Entering into the unknown to me — but known to ideas.

LG: Where in the country were you?

AMN: Perris, California. My husband and I had five beautiful kids and we lived on an acre and a half of land. Dogs and horses, space and clear skies… with Francisco I didn’t know I was writing a book. I know I sound presumptuous, or even possibly arrogant, but it’s in a pure sense. I just obeyed. And what I did know was that this was my creative outlet. That it was me keeping in touch with my art, me keeping in touch with me. I wasn’t saying, “I’m writing about my journey with Newman.” Oh my god, no. Or, “I’m going to write about this young Black filmmaker struggling to make this film.” (laughter) None of that. But I will say, that subliminally, as I kept writing, I started to believe in it, that it was something. It was like a whisper, or a glimpse, like a faraway melody that I could barely hear, that encouraged me to keep writing.

LG: You found time for yourself, and your craft. Absolutely.

AMN: And then one day Ishmael came over for a meeting with Newman. I had been writing but I scurried out of the room for some reason and my writing was all on the table.

It was such a fun new thing to just be a lover, and cooking, and washing dishes, and supporting Francisco, it was so beautiful. When I read some of the comments that I lost myself — no, no, no, no, no. That I was idle — no, no. Do you see how I answered the call? I was writing even though I didn’t know it was a book, I was still writing. I stuck to it with all the shenanigans and ups and down, and going here and there, I stuck to it. As a result, to my wonderful surprise, it became what it is today. Trust in the hidden plans for your life. Trust the voice in you that tells you to write, or make a movie, or write a song, a career, a business ... or that he’s the one, or that he isn’t the one, or whatever.

LG: No, you were not idle. That’s not what I take from those pages. Mmhmm.

AMN: It was a different creative mode, and it was a different season. Life can have many new seasons if you’re blessed to keep living. People need to consider if they just value someone for being famous. Is that the value that you have for artists, or creativity, or a human being? Can you not value someone in the process of becoming, in the process of working toward discovering something or just because they are alive? There are diverse goals, roads, paths, and Hollywood might not even be the place where God wants you to be, it might not be for you. It may destroy you. So, what are you talking about that I was idle? I didn’t lose myself. I held on to myself… yet in duality, in another way I submit I was lost… lost in sin and in need of salvation… but I held on to who I believe I knew I was from my childhood. My father was a scientist and initially I wanted to be a scientist. He became my biggest fan later on but when I came to the dinner table one day and said I wanted to be an actress, he said, “Absolutely not.” He straight up said, “Actresses are whores.” When I had all these moments, with directors and producers, when they wanted me to betray my values, I heard my father’s voice.

LG: Like a prophecy, it felt like.

AMN: Yeah, it was prophetic. Hold on to you. Hold on to what you know is right. Don’t sell your soul for the love of money or fame. Find another way. I, innocently, was looking for another way. When I look back at myself at nineteen and twenty I thank her. I read some reviews and they say that I denounced Francisco. I did not denounce the book in my afterward. I denounced the lifestyle, the profanity of my youth. When I read the book again at the age of seventy-two there were some places that shocked me. But as I continued to read, it’s still the same heart looking for the answer, looking for the love, and looking for the way. Life can be a continuum of letting go.

LG: You had to be her to get to you.

As a writer, what is your current practice? Do you write every day?

AMN: Probably three or four times a week. I’m a big believer in consistency. Writing is a dear friend and comfort. I’ve heard people talk about writing block but I don’t experience that because I don’t consider space being a block.

LG: Interesting. I love that.

AMN: If I don’t write for a day, or even if it ends up being a few days, I just feel like I’m living. There’s something I’ve got to move in, I’ve got to swim in. I don’t experience writing blocks; I experience space or rest where I’m just listening… waiting… then I hear it and I get to it, I write it.

I’m disciplined in that I just keep at it. I’m always conscious of creativity, I can be anywhere and see, feel it; it’s always around us. I’m listening with anticipation, what’s next? It’s also that I have freedom. I pretty much live alone; I’m a widow. So, I might wake up at three in the morning and write to ten non-stopping, caught up in the receiving, refining, perfecting, searching for words. It’s kind of a free flow, but it’s also being reminded of things I’ve written in the past that can fit what I’m doing in the present. Go get it. Go find it. I end up putting it together and it works… at least to me.

LG: It reveals itself. Back to your memory — you held on to that.

AMN: It happens to me so often. That’s my writing process, but my style (laughter), it’s musical. With Ishmael and Ornette and Frank Silvera, I was supported in my style, I was supported in me. They didn’t change a note. I’m so grateful for that. I wish these publishers and producers would do that for others.

LG: Me too. I go back to richness: it just gets edited out because people are looking at what will sell, and what is a woman’s story and what is a Black story and what is a brown story instead of looking at what is the story?

AMN: What they don’t do is let people talk, and when they do talk, “How dare you.” But if we let people talk and listen and remember to agree to disagree there’s the hope we can grow in love and understand each other’s pain and joys and learn something, even be transformed, corrected, changed. Jesus commands to forgive and love your neighbor. People always say Francisco is the only book I wrote. Well, it’s not the only book; I’ve got a few manuscripts, poetry, unpublished stuff. We have to work on enlightening the consciousness of publishers. People bought Francisco!

LG: Books find their readers. They find them. We find what we need.

AMN: Yeah. Yeah. So let it be… let artists breathe and tell their stories whether you agree or disagree.

Lead Photo: Francisco Newman and Alison Mills Newman on Second Street in New York with their children Daniel and Leaf. c.1976-78. Photo: Chantal Renault.